One of our most anticipated exhibitions will concentrate on Photonovels in Western and Non-Western contexts. Hosted by the public library and culture center Dokk1 and curated by Frédérique Deschamps & Olubukola Gbadegesin, it will feature fine examples of this often underrated genre of visual storytelling:

It was 1947. Italy had barely emerged from five years of war, a defeated nation, much of it still in ruins. Just about everything was still subject to rationing, including paper. And yet, it was in the midst of this period of deprivation that a few clever souls invented the photo-novella. They understood that, more than anything else, Italy needed to dream. Their serialized, sentimental tales of love primarily targeted a female audience, Italian women having become consumers after gaining a measure of independence during the war.

Before being a movie actress, Sofia Loren appeared in several « fotoromanzi » in the 1950’s. Collection Roberto Baldazzini

The success of the photo-novella was immediate, surprising even its creators who were sometimes obliged to hastily reprint sold-out issues. These black and white soap operas were churned out by the millions. They used top of the line cameras – Rolleiflex, Mamiya or, later, Hasselblad – and 6×6 or 6×9 film formats, but production long remained an artisanal process. Scenes were flash lighted, sometimes requiring 3 or 4 flashbulbs for a single shot. Once developed, the selected images were printed, cropped, retouched with gouache, and pasted on cardboard, all by hand. The speech balloons, handwritten at first and later typed, were glued on later.

Contact of a photograph for the italian photo-novella « Una mano per chi soffre », 1961, with indications for cropping the picture. © Alberto Mondadori editore

Looking at the pictures in photo-novellas one immediately thinks of movies, yet here movement is frozen, whereas it is the very essence of cinema. The storyline was presented in the foreground, so it could be quickly grasped, with images often cropped and reframed to emphasize the essential. Feelings and the inner conflicts of characters were portrayed melodramatically. What little background existed was usually quite bare and served essentially to establish context: a palm tree for tropical climes, a chandelier for a castle, a car to indicate social status, and so on.

In 1949, Michelangelo Antonioni made L’Amorosa Menzogna, a 10-minute documentary about this new phenomenon in Italian society. Working with a handheld camera, he filmed darkroom techniques, visited printing plants, and followed two actors who had already attained star status: Anna Vita and Sergio Raimondi. Antonioni also wrote the original script for another film, The White Sheik, a fierce satire of the photo-novella that Federico Fellini made into a film in 1952.

But in many quarters, the photo-novella drew people’s wrath. Intellectuals considered it a sub-genre of literature that was not just abject, but dangerous. “True life may well be found in dreams, but dreams can plunge us to fatal depths”, moans Wanda, the bambola appassionata in Federico Fellini’s White Sheik, after she is nearly raped by a turbaned photo-novella actor played by Alberto Sordi.

Ektachrome of an italian photo-novella from the 1960’s by Piero Orsola. Collection Frédérique Deschamps

For Catholics, the photo-novella was plainly immoral. It showed unmarried couples kissing and women abandoning their marital homes, at a time when under Italian law women could be sentenced to two years in prison for adultery, which remained the case until 1968. In 1959, Pope John XXIII issued a papal encyclical (Ad Petri Cathedram) warning his followers to be wary of “books and magazines written to mock virtue and exalt depravity.”

As for the Communists, this was just another kind of opium for the masses, and thereby an impediment to class struggle and social revolution, for as opposed to the neorealism of Italian cinema, which emerged at the same time, the contemporary social and political situation was never condemned. As one French historian put it, “There was no such thing as revolt in the photo-novella.”

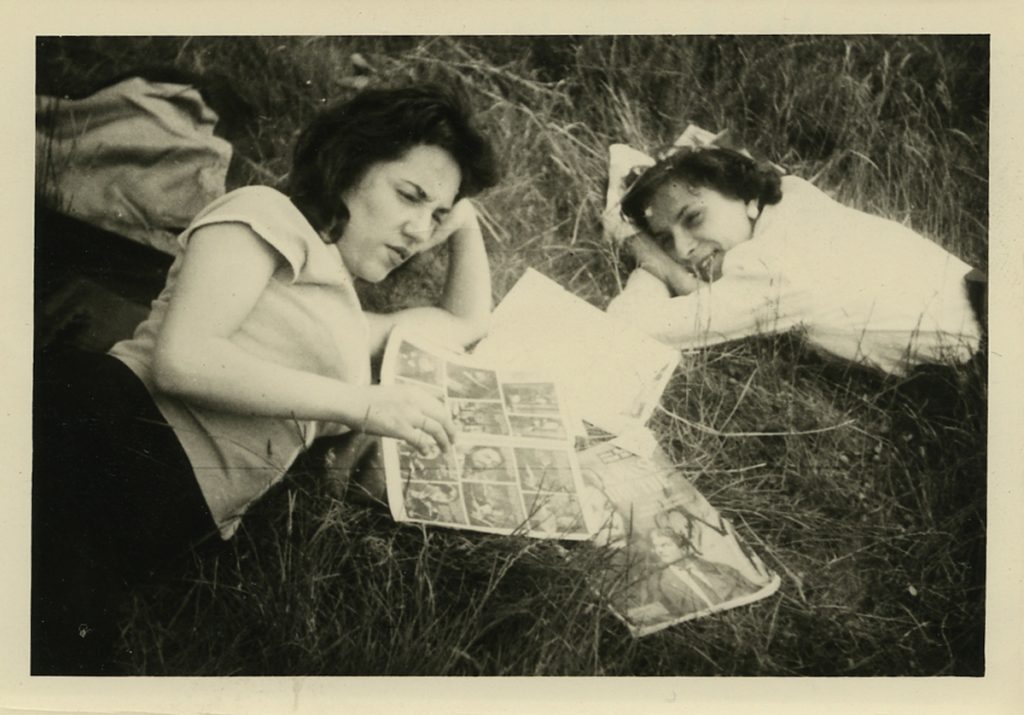

Young women reading photo-novellas in the 1950’s. Collection Frédérique Deschamps

As we look upon these frothy love stories today, they hardly seem to deserve such sarcasm and virulent criticism. The reasons for the ire they drew are perhaps to be found in Pierre Bourdieu’s writings. “…when they have to be justified, [tastes] are asserted purely negatively, by the refusal of other tastes. In matters of taste, more than anywhere else, all determination is negation; and tastes are perhaps first and foremost distastes, disgust provoked by horror or visceral intolerance of the tastes of others.” To which he added, “Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier.” (Pierre Bourdieu , Distinction – A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, 1979)

The photo-novella was entertainment for the lower classes, and was intended as such, which is probably why it often makes us smile. But it also served as a remarkable mirror to the beginnings of Italy’s unprecedented economic boom, consumerist culture, women’s liberation, the society of the spectacle, and so on. The use of photographs, which gives photo-novellas their modern feel and undoubtedly accounted in large part for their huge commercial success, provided a physical dimension to the stories they told and rooted them in the present, replete with all the postwar markers of happiness: cars, television sets, refrigerators, juke boxes, fur coats….

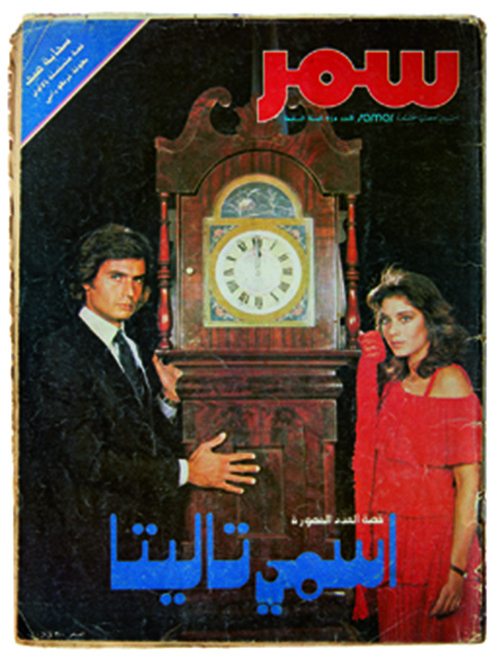

Cover of Samar, a lebanese magazine with italian photo-novellas, 1980. Collection Frédérique Deschamps

The stories of jealousy, betrayal, lies, and triumphant love that photo-novellas depicted were universal. Soon after the creation of the genre in 1947 Italy began exporting them. They were replicated throughout the world, in France, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Turkey, Lebanon, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and elsewhere, after which several countries began producing their own.

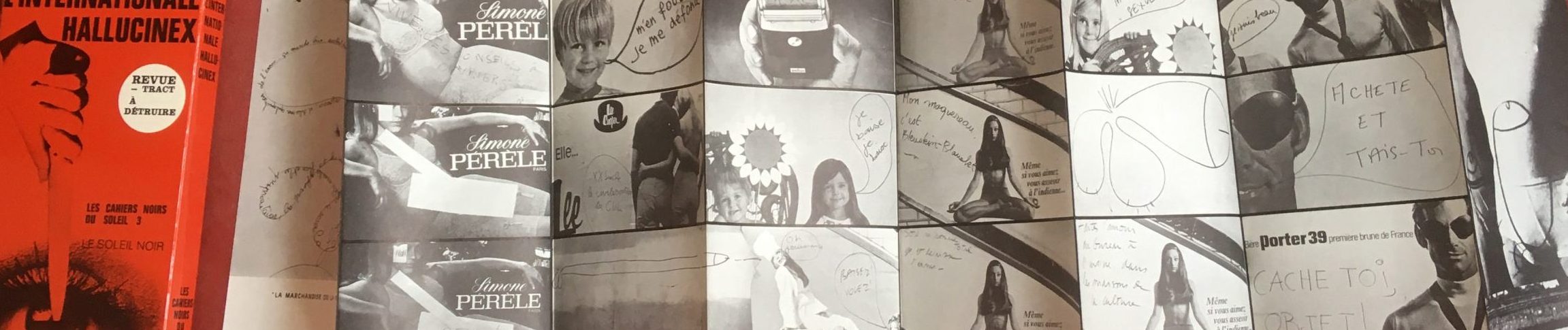

The photo-novella enjoyed phenomenal success for a quarter of a century. And today it is making a comeback. Situationists, pornographers and satirists have appropriated its style for works that are far more than simple love stories with a happy ending.

Frédérique Deschamps

–

A special case of the genre is the Nigerian photoplays, which can be considered the first genuine African photonovels. Yorùbá theatre practitioners employed the print media and the unique production medium was responsible for an impressive output of magazines and books during the second half of the twentieth century. Today we can say that these translocal adaptations of international forms had a tremendous impact on regional and national senses of cultural and political identity, at the dawn of colonial independence:

In Nigeria, the Yoruba Photoplay Series sprung from three sites of origin—photonovellas, indigenous Yoruba travelling theatre, and African literature. The first debt is owed to post-war Italian photonovellas which moved through colonial channels to South African markets in the 1960s. Known there as “look-reads”, they were hugely popular and soon caught on in Nigeria, where they inspired the layout of photoplays. Credit is also due to Hubert Ogunde who pioneered the influential Yoruba travelling theatre form in 1946. Following his lead, acting troupes toured small towns in the countryside. They put on comical, moral, mythic, or political plays that became a huge hit with lively Yoruba audiences. These plays supplied the stories printed in the magazines, along with a growing body of African literature. Printed novels, plays and poetry—especially those written in the Yoruba language—were very popular from the 1940s on. Anti-colonial energies boosted indigenous publications. Together, language and education were lifted up as primary pillars of post-independence prosperity.

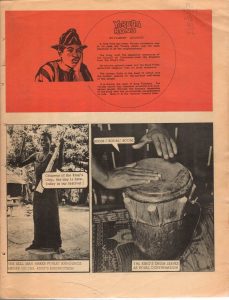

Making photoplays was a joint effort by the editor of the series, the troupe leader, actors, and the photographer who captured the scenes. The editor was Segun Sofowote, a theatre doyen who selected which troupe leader would be featured. The series photographer, Abimbade Ọladejọ, would scout locations and take the pictures. On the scheduled day, the troupe performed the play, pausing to pose dramatically for pictures at key moments. There was no script. It was all improvised, just like with the live plays. Then, with the shoot finished, Sofowote wrote the texts, prepared the layout, and approved the printing. West African Book Publishing—founded by American ex-pat Richard Gamble—produced the series from 1967 through the late 1980s.

When the photoplays were first published, Nigeria was in a state of cultural change and political crisis. Within a decade of independence from Britain in 1960, the first of several coups had taken place. Earlier, the country had buzzed with possibilities—of self-determination, national unity, oil wealth, exciting educational initiatives, and improved social welfare. Later, ethnic tensions dogged the new federal government. Ethno-centricism overshadowed a budding sense of national identity. The crisis soon came to a head in 1967 when the Biafran civil war broke out—just as the first issues of the Yoruba Photoplay Series were published in Lagos.

On bustling streets, in open air markets, at their desks, and on crowded buses, Lagosians read the first issues of Yoruba Photoplay Series. The series was so popular for so long in part because they allowed readers to participate in a modern, popular culture. They were tangible symbols of modernity set against the backdrop of traditional codes and practices. But also, they were legible to a growing, but not totally, literate Yoruba readership. Only the first issue was printed in English and Yoruba—the latter sold much better than the former. All subsequent issues were written in standard Yoruba, a conscious attempt to re-center an indigenous cultural heritage after decades of colonial rule. As a genre, the photoplays were known locally as “iwe alaworan”, which translates loosely to “picture book.” And they were made for a reading public that extended beyond the written word, to images, which could also be “read.”

Panels 1 & 2 in English edition “Yoruba Ronu” vol. 1, no. 1 (Lagos, Nigeria: West African Book Publishers, 1967; unpaginated)

Photoplays were both timely and timeless in the way that they invited readers into currently unfolding stories. In 1971, a prefix was added to the name and it became Atoka: The Yoruba Photoplay Series. Meaning, “to point at”, atoka was a term that highlighted the magazine’s mission as social commentary, with readers in tow. Indeed, the second issue of “Oju Eni Ma La” (vol.13) opens with a call for the readers to rejoin the developing story: “E maa kaa lọ” ( “Come along with us”). Here, the story is reframed as an excursion, a journey of revelation and understanding undertaken by readers and narrator alike. This standing invitation to the story is never rescinded—any reader may return to the photoplay, decades later, and be greeted with the same ever-present welcome. And readers responded enthusiastically to these invitations.

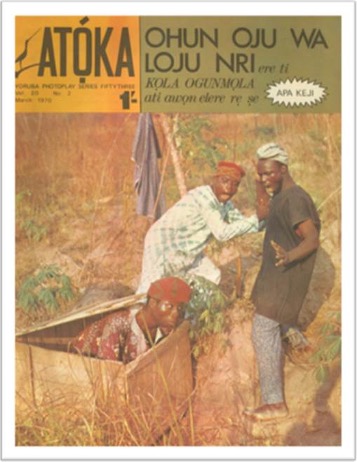

Cover page, “Ohun Oju Wa Loju Nri” vol. 10, no. 2 (Lagos, Nigeria: West African Book Publishers, 1967; unpaginated)

Over time, photoplays also nurtured a co-creative relationship with their audiences. Readers saw the magazines as a source of knowledge and life lessons, not just commodities. Metaphorically and literally, readers wanted to see themselves in its pages. And by 1971, readers started to write letters to the editor that were printed alongside the featured stories. Some asked for advice from other readers and the editor. Other writers shared their own tangled tales of woe—often as dramatic as the photoplays. A few asked about starting “reading clubs” where loyal reader could meet and discuss the photoplays in more detail.

Letters to the Editor (1971. “Iyawo Alalubosa…”, vol. 27, no. 4: p. 1

In the late 1980s, the rise of the video-film industry and rising costs of production overtook the publication and forced its demise. But here and there, stray copies of the photoplays remain in private hands, where they were first made meaningful. Recently, a photoplay was recovered in a long-lost suitcase left behind in Spain by a Nigerian national, Prince Emmanuel Adewale Oyenuga. May the return of the suitcase and the photoplay to extended family in Nigeria herald the return of these once-beloved pages to our hearts.

This show will also contain several issues of the Yoruba Photoplay Series (incl. Yoruba Rono, Oba Koso, Omuti, Ologbo Dudu, Asiko Na To); An original novel (Palm Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola); A original issue of African Film magazine (with Lance Spearman); and an original issue of Magnet: The Yoruba Photoplay Magazine (with Johnny “Thunderman” Nelson).

Join us and experience Passion, Violence, Drama, Charm, and Treason from around the world and in its most splendid text-image representations.